Ancient Ships And Navigators

Everything must have a beginning, and, however right and proper things may appear to those who begin them, they generally wear a strange, sometimes absurd, aspect to those who behold them after the lapse of many centuries.

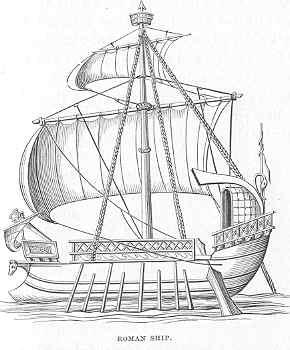

When we think of the trim-built ships and yachts that now cover the ocean far and wide, we can scarce believe it possible that men really began the practice of navigation, and first put to sea, in such grotesque vessels as that represented on page 55.

In a former chapter reference has been made to the rise of commerce and maritime enterprise, to the fleets and feats of the Phoenicians, Egyptians, and Hebrews in the Mediterranean, where commerce and navigation first began to grow vigorous. We shall now consider the peculiar structure of the ships and boats in which their maritime operations were carried on.

Boats, as we have said, must have succeeded rafts and canoes, and big boats soon followed in the wake of little ones. Gradually, as men’s wants increased, the magnitude of their boats also increased, until they came to deserve the title of little ships. These enormous boats, or little ships, were propelled by means of oars of immense size; and, in order to advance with anything like speed, the oars and rowers had to be multiplied, until they became very numerous.

In our own day we seldom see a boat requiring more than eight or ten oars. In ancient times boats and ships required sometimes as many as four hundred oars to propel them.

The forms of the ancient ships were curious and exceedingly picturesque, owing to the ornamentation with which their outlines were broken, and the high elevation of their bows and sterns.

We have no very authentic details of the minutiae of the form or size of ancient ships, but antiquarians have collected a vast amount of desultory information, which, when put together, enables us to form a pretty good idea of the manner of working them, while ancient coins and sculptures have given us a notion of their general aspect. No doubt many of these records are grotesque enough, nevertheless they must be correct in the main particulars.

Homer, who lived 1000 B.C., gives, in his “Odyssey,” an account of ship-building in his time, to which antiquarians attach much importance, as showing the ideas then prevalent in reference to geography, and the point at which the art of ship-building had then arrived. Of course due allowance must be made for Homer’s tendency to indulge in hyperbole.

Ulysses, king of Ithaca, and deemed on of the wisest Greeks who went to Troy, having been wrecked upon an island, is furnished by the nymph Calypso with the means of building a ship,—that hero being determined to seek again his native shore and return to his home and his faithful spouse Penelope.

“Forth issuing thus, she gave him first to wield

A weighty axe, with truest temper steeled,

And double-edged; the handle smooth and plain,

Wrought of the clouded olive’s easy grain;

And next, a wedge to drive with sweepy sway;

Then to the neighbouring forest led the way.

On the lone island’s utmost verge there stood

Of poplars, pines, and firs, a lofty wood,

Whose leafless summits to the skies aspire,

Scorched by the sun, or seared by heavenly fire

(Already dried). These pointing out to view,

The nymph just showed him, and with tears withdrew.

“Now toils the hero; trees on trees o’erthrown

Fall crackling round, and the forests groan;

Sudden, full twenty on the plain are strewed,

And lopped and lightened of their branchy load.

At equal angles these disposed to join,

He smoothed and squared them by the rule and line.

(The wimbles for the work Calypso found),

With those he pierced them and with clinchers bound.

Long and capacious as a shipwright forms

Some bark’s broad bottom to outride the storms,

So large he built the raft; then ribbed it strong

From space to space, and nailed the planks along.

These formed the sides; the deck he fashioned last;

Then o’er the vessel raised the taper mast,

With crossing sail-yards dancing in the wind:

And to the helm the guiding rudder joined

(With yielding osiers fenced to break the force

Of surging waves, and steer the steady course).

Thy loom, Calypso, for the future sails

Supplied the cloth, capacious of the gales.

With stays and cordage last he rigged the ship,

And, rolled on levers, launched her on the deep.”

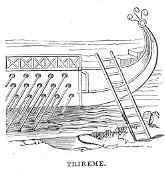

The  ships of the ancient Greeks and Romans were divided into various classes, according to the number of “ranks” or “banks,” that is, rows, of oars. Monoremes contained one bank of oars; biremes, two banks; triremes, three; quadriremes, four; quinqueremes, five; and so on. But the two latter were seldom used, being unwieldy, and the oars in the upper rank almost unmanageable from their great length and weight.

ships of the ancient Greeks and Romans were divided into various classes, according to the number of “ranks” or “banks,” that is, rows, of oars. Monoremes contained one bank of oars; biremes, two banks; triremes, three; quadriremes, four; quinqueremes, five; and so on. But the two latter were seldom used, being unwieldy, and the oars in the upper rank almost unmanageable from their great length and weight.

Ptolemy Philopator of Egypt is said to have built a gigantic ship with no less than forty tiers of oars, one above the other! She was managed by 4000 men, besides whom there were 2850 combatants; she had four rudders and a double prow. Her stern was decorated with splendid paintings of ferocious and fantastic animals; her oars protruded through masses of foliage; and her hold was filled with grain!

That this account is exaggerated and fanciful is abundantly evident; but it is highly probable that Ptolemy did construct one ship, if not more, of uncommon size.

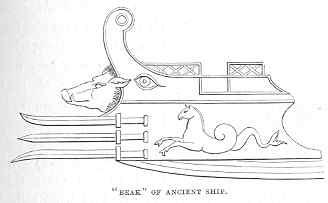

The  sails used in these ships were usually square; and when there was more than one mast, that nearest the stern was the largest. The rigging was of the simplest description, consisting sometimes of only two ropes from the mast to the bow and stern. There was usually a deck at the bow and stern, but never in the centre of the vessel. Steering was managed by means of a huge broad oar, sometimes a couple, at the stern. A formidable “beak” was affixed to the fore-part of the ships of war, with which the crew charged the enemy. The vessels were painted black, with red ornaments on the bows; to which latter Homer is supposed to refer when he writes of red-cheeked

sails used in these ships were usually square; and when there was more than one mast, that nearest the stern was the largest. The rigging was of the simplest description, consisting sometimes of only two ropes from the mast to the bow and stern. There was usually a deck at the bow and stern, but never in the centre of the vessel. Steering was managed by means of a huge broad oar, sometimes a couple, at the stern. A formidable “beak” was affixed to the fore-part of the ships of war, with which the crew charged the enemy. The vessels were painted black, with red ornaments on the bows; to which latter Homer is supposed to refer when he writes of red-cheeked  ships.

ships.

Ships built by the Greeks and Romans for war were sharper and more elegant than those used in commerce; the latter being round bottomed, and broad, in order to contain cargo.

The Corinthians were the first to introduce triremes into their navy (about 700 years B.C.), and they were also the first who had any navy of importance. The Athenians soon began to emulate them, and ere long constructed a large fleet of vessels both for war and commerce.  That these ancient ships were light compared with ours, is proved by the fact that when the Greeks landed to commence the siege of Troy they drew up their ships on the shore. We are also told that ancient mariners, when they came to a long narrow promontory of land, were sometimes wont to land, draw their ships bodily across the narrowest part of the isthmus, and launch them on the other side.

That these ancient ships were light compared with ours, is proved by the fact that when the Greeks landed to commence the siege of Troy they drew up their ships on the shore. We are also told that ancient mariners, when they came to a long narrow promontory of land, were sometimes wont to land, draw their ships bodily across the narrowest part of the isthmus, and launch them on the other side.

Moreover, they had a salutary dread of what sailors term “blue water”—that is, the deep, distant sea—and never ventured out of sight of land. They had no compass to direct them, and in their coasting voyages of discovery they were guided, if blown out to sea, by the stars.

The sails were made of linen in Homer’s time; subsequently sail-cloth was made of hemp, rushes, and leather. Sails were sometimes dyed of various colours and with curious patterns. Huge ropes were fastened round the ships to bind them more firmly together, and the bulwarks were elevated beyond the frame of the vessels by wicker-work covered with skins.

Stones were used for anchors, and sometimes crates of small stones or sand; but these were not long of being superseded by iron anchors with teeth or flukes.

The Romans were not at first so strong in naval power as their neighbours, but in order to keep pace with them they were ultimately compelled to devote more attention to their navies. About 260 B.C. they raised a large fleet to carry on the war with Carthage. A Carthaginian quinquereme which happened to be wrecked on their coast was taken possession of by the Romans, used as a model, and one hundred and thirty ships constructed from it. These ships were all built, it is said, in six days; but this appears almost incredible. We must not, however, judge the power of the ancients by the standard of present times. It is well known that labour was cheap then, and we have recorded in history the completion of great works in marvellously short time, by the mere force of myriads of workmen.

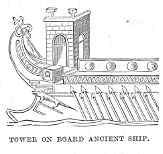

The Romans not only succeeded in raising a considerable navy, but they proved themselves ingenious in the contrivance of novelties in their war-galleys.  They erected towers on the decks, from the top of which their warriors fought as from the walls of a fortress. They also placed small cages or baskets on the top of their masts, in which a few men were placed to throw javelins down on the decks of the enemy; a practice which is still carried out in principle at the present day, men being placed in the “tops” of the masts of our men-of-war, whence they fire down on the enemy. It was a bullet from the “top” of one of the masts of the enemy that laid low our greatest naval hero, Lord Nelson.

They erected towers on the decks, from the top of which their warriors fought as from the walls of a fortress. They also placed small cages or baskets on the top of their masts, in which a few men were placed to throw javelins down on the decks of the enemy; a practice which is still carried out in principle at the present day, men being placed in the “tops” of the masts of our men-of-war, whence they fire down on the enemy. It was a bullet from the “top” of one of the masts of the enemy that laid low our greatest naval hero, Lord Nelson.

From this time the Romans maintained a powerful navy. They crippled the maritime power of their African foes, and built a number of ships with six and even ten ranks of oars. The Romans became exceedingly fond of representations of sea-fights, and Julius Caesar dug a lake in the Campus Martius specially for these exhibitions. They were not by any means sham fights. The unfortunates who manned the ships on these occasions were captives or criminals, who fought as the gladiators did—to the death—until one side was exterminated or spared by imperial clemency. In one of these battles no fewer than a hundred ships and nineteen thousand combatants were engaged!

Such were the people who invaded Britain in the year 55 B.C. under Julius Caesar, and such the vessels from which they landed upon our shores to give battle to the then savage natives of our country.

It is a curious fact that the crusades of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries were the chief cause of the advancement of navigation after the opening of the Christian era. During the first five hundred years after the birth of our Lord, nothing worthy of notice in the way of maritime enterprise or discovery occurred.

But about this time an event took place which caused the foundation of one of the most remarkable maritime cities in the world. In the year 476 Italy was invaded by the barbarians. One tribe, the Veneti, who dwelt upon the north-eastern shores of the Adriatic, escaped the invaders by fleeing for shelter to the marshes and sandy islets at the head of the gulf, whither their enemies could not follow by land, owing to the swampy nature of the ground, nor by sea, on account of the shallowness of the waters. The Veneti took to fishing, then to making salt, and finally to mercantile enterprises. They began to build, too, on those sandy isles, and soon their cities covered ninety islands, many of which were connected by bridges. And thus arose the far-famed city of the waters—“Beautiful Venice, the bride of the sea.”

Soon the Venetians, and their neighbours the Genoese, monopolised the commerce of the Mediterranean.

The crusades now began, and for two centuries the Christian warred against the Turk in the name of Him who, they seem to have forgotten, if indeed the mass of them ever knew, is styled the Prince of Peace. One of the results of these crusades was that the Europeans engaged acquired a taste for Eastern luxuries, and the fleets of Venice and Genoa, Pisa and Florence, ere long crowded the Mediterranean, laden with jewels, silks, perfumes, spices, and such costly merchandise. The Normans, the Danes, and the Dutch also began to take active part in the naval enterprise thus fostered, and the navy of France was created under the auspices of Philip Augustus.

The result of all this was that there was a great moving, and, to some extent, commingling of the nations. The knowledge of arts and manufactures was interchanged, and of necessity the knowledge of various languages spread. The West began constantly to demand the products of the East, wealth began to increase, and the sum of human knowledge to extend.

Shortly after this era of opening commercial prosperity in the Mediterranean, the hardy Northmen performed deeds on the deep which outrival those of the great Columbus himself, and were undertaken many centuries before his day.

The Angles, the Saxons, and the Northmen inhabited the borders of the Baltic, the shores of the German Ocean, and the coasts of Norway. Like  the nations on the shores of the Mediterranean, they too became famous navigators; but, unlike them, war and piracy were their chief objects of pursuit. Commerce was secondary.

the nations on the shores of the Mediterranean, they too became famous navigators; but, unlike them, war and piracy were their chief objects of pursuit. Commerce was secondary.

In vessels resembling that of which the above is a representation, those nations went forth to plunder the dwellers in more favoured climes, and to establish the Anglo-Saxon dominion in England; and their celebrated King Alfred became the founder of the naval power of Britain, which was destined in future ages to rule the seas.

It was the Northmen who, in huge open boats, pushed off without chart or compass (for neither existed at that time) into the tempestuous northern seas, and, in the year 863, discovered the island of Iceland; in 983, the coast of Greenland; and, a few years later, those parts of the American coast now called Long Island, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland. It is true they did not go forth with the scientific and commercial views of Columbus; neither did they give to the civilised world the benefit of their knowledge of those lands. But although their purpose was simply selfish, we cannot withhold our admiration of the bold, daring spirit displayed by those early navigators, under circumstances of the greatest possible disadvantage—with undecked or half-decked boats, meagre supplies, no scientific knowledge or appliances, and the stars their only guide over the trackless waste of waters.

In the course of time, one or two adventurous travellers pushed into Asia, and men began to ascertain that the world was not the insignificant disc, or cylinder, or ball they had deemed it. Perhaps one of the chief among those adventurous travellers was Marco Polo, a Venetian, who lived in the latter part of the thirteenth century. He made known the central and eastern portions of Asia, Japan, the islands of the Indian Archipelago, part of the continent of Africa, and the island of Madagascar, and is considered the founder of the modern geography of Asia.

The adventures of this wonderful man were truly surprising, and although he undoubtedly exaggerated to some extent in his account of what he had seen, his narrations are for the most part truthful. He and his companions were absent on their voyages and travels twenty-one years.

Marco Polo died; but the knowledge of the East opened up by him, his adventures and his wealth, remained behind to stir up the energies of European nations. Yet there is no saying how long the world would have groped on in this twilight of knowledge, and mariners would have continued to “hug the shore” as in days gone by, had not an event occurred which at once revolutionised the science of navigation, and formed a new era in the history of mankind. This was the invention of the mariner’s compass.

Previous: Rafts And Canoes

Next: The Mariner’s Compass—portuguese Discoveries

|

|

| SHARE | |

|

|

| ADD TO EBOOK |